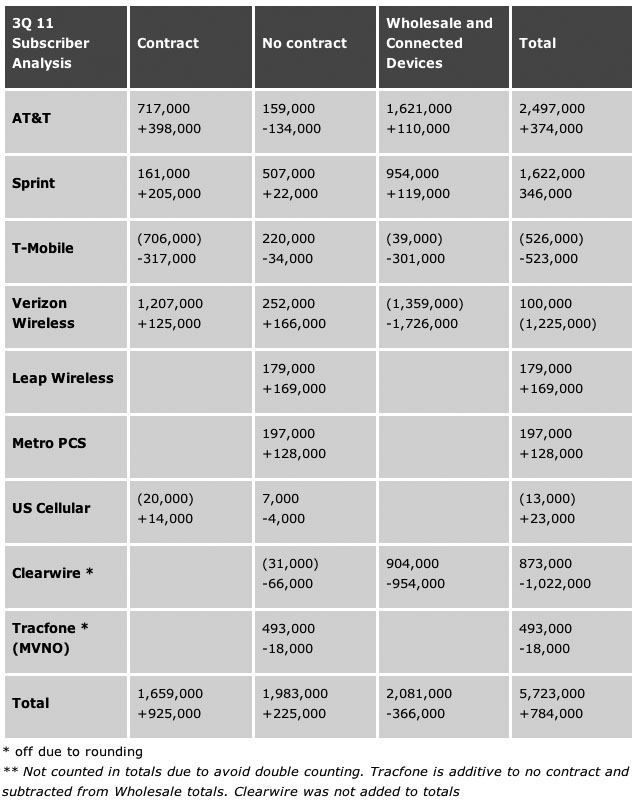

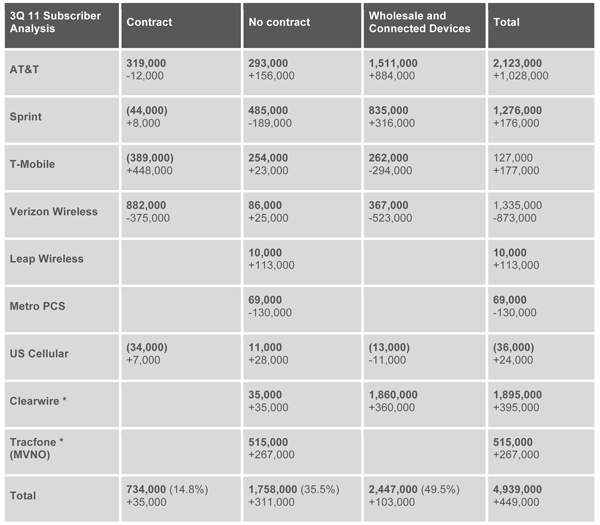

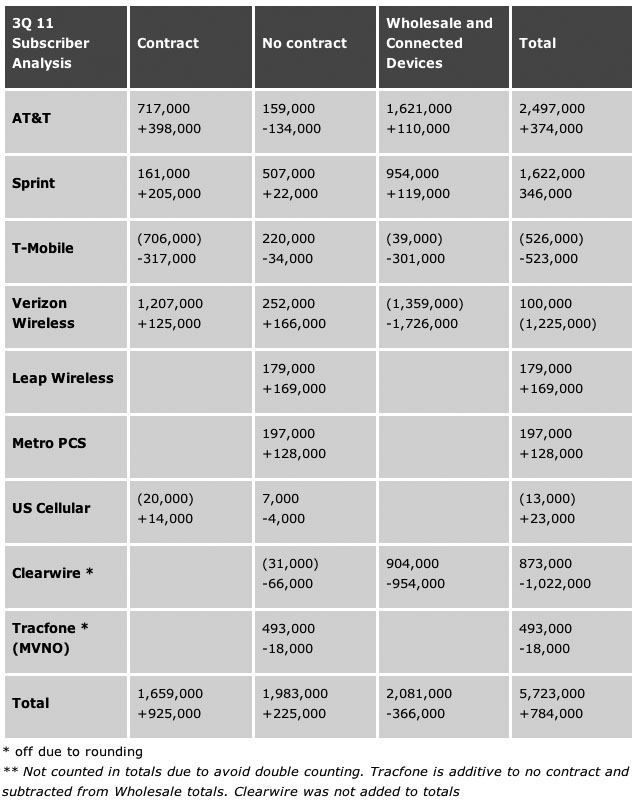

- The fourth quarter of 2011 was excellent for the wireless industry. More than 5.7 million net additions in the quarter were fueled by the iPhone 4S launch, demonstrating that massive growth is still possible in wireless. This is welcome news for handset makers, app developers, operators and network vendors alike. AT&T beat its best smartphone sales by more than 50percent in the quarter, Verizon Wireless had the best contract quarter in three years and Sprint had the best subscriber addition numbers since 2005.

- The launch of the iPhone 4S and the impact it had on the fortunes of the wireless operators, especially Sprint and T-Mobile, made it clear who is the king maker in wireless: Apple–as long as nobody else starts to develop something different and completely magical.

- Sprint as the most recent “iPhone have” gained contract customers for the first time in almost six years. At the same time, the woes of T-Mobile, as the last remaining nationwide “iPhone have-not” got worse. Customers left T-Mobile in large numbers on the heels of the iPhone 4S launch and the failed acquisition by AT&T.

- Verizon and AT&T attracted the most contract customers, while Sprint and Tracfone attracted the most non-contract customers. AT&T and Sprint were most successful in attracting wholesale and connected device customers.

- Who would have thought that Sprint would add 16-times more total customers in the fourth quarter of 2011 than Verizon?

- The failed acquisition leaves T-Mobile the most vulnerable operator. With mounting customer losses, six months to two years behind the competition in 4G LTE and lukewarm support from its parent, life will be hard for the Seattle-based operator. Will they be able to make it alone or will a new suitor appear?

- US Cellular is in a precarious situation as it is also behind with its 4G LTE network. In addition, it has to find a reason why people should join them, and it must do that quickly.

- Clearwire has to execute like it has never executed before. Squandering a two-year lead on 4G (WiMAX) was bad enough. Now its strategic investors are bailing. The company has to build its 4G LTE network quickly to give Sprint enough of a reason to put the unique LTE Clearwire technology in enough of its devices. Without Sprint, Clearwire is dead. Better forget all the romanticized rumors of another white knight carrier coming along to come to the rescue of Clearwire. We have heard it before–many times over the years. Sprint is all you’ve got.

- The opposition of the Department of Justice and FCC against the acquisition of T-Mobile by AT&T and the similar front lines appearing against the sale of the previously unused cable company spectrum by Verizon Wireless leaves one to wonder how successful carriers are supposed to get the spectrum they need to satisfy their customer’s demands.

AT&T (NYSE:T) had a gangbuster quarter. It added 9.4 million smartphones in the quarter alone, smashing its previous smartphone record by 50 percent. On the heels of the iPhone 4S launch, AT&T more than doubled contract subscriber additions to 717,000 for the quarter. AT&T leads the industry with 56.8 percent of contract customers using a smartphone. Even though Sprint launched the iPhone for the first time, churn stayed muted at 1.4 percent. This shows that there is a significant disconnect between the negative press coverage that AT&T continues to receive and how customers are actually behaving as existing customers stay with AT&T near record low numbers and large numbers of new subscribers are joining them. Surprisingly, prepaid was weak for the quarter, as prepaid phones are often given as holiday gifts, making December 25 typically the day with the most activations in the year. While Santa seems to have come up short on the prepaid side, the wholesale and connected group made massive gains. Since AT&T dominates the e-reader segment this has been largely driven by Amazon Kindles and Barnes & Noble Nooks.

In January 2012, AT&T introduced new data plans during the quarter. Customers get 50 percent more data for $5 more. There was widespread confusion and misreporting in the press regarding the motivations behind this change. The pricing move has to be looked at through the prism of declining operating margins, which plummeted from 22.9 percent last year to 15.2 percent. The reason for the decline in operating margin is smartphone handset subsidies. AT&T has to slow down the smartphone conversion rate to improve its operating margins as the typical smartphone comes with a $200 to $450 device subsidy. Early adopters and mainstream customers motivated by technical novelty and value have become smartphone users, driving ARPU significantly up. Technology laggards and less affluent customers still using feature phones remain to be converted. For these feature phone users, price is a major motivating factor if they are converting to a smartphone. By increasing the monthly recurring charge the conversion rate especially from their own feature phone base is going to slow down and margins are going to begin to improve due to a better revenue to subsidy ratio.

Santa was very good to Sprint (NYSE:S) in the fourth quarter. Sprint had the most customer additions in the last seven years. APRU went up by $3.68, the highest of any operator in the United States. Also, Sprint finally gained contract customers. The company now has more customers than ever and has officially recovered from its disastrous merger with Nextel six and a half years ago. While the Nextel platform is in terminal decline and continues to lose customers, the Sprint network is adding more and more customers. Sprint sold more than 1.8 million iPhones in the fourth quarter, and 40 percent of iPhone sales were to new Sprint customers. This translates into roughly 720,000 customers, which was substantially more than the 161,000 net contract additions. Numbers like that show that the power in the wireless industry has clearly shifted towards the makers of blockbuster devices. Without the iPhone it is quite likely that Sprint would have continued to lose customers in the fourth quarter. What is concerning is that the percentage of prime postpaid customers on Sprint declined from 83 percent to 82 percent, which is roughly 330,000 customers. This means that twice as many sub-prime customers became new postpaid customers at Sprint than the company had contract net additions. While Sprint was focusing on selling new iPhones, its sales of 4G WiMAX devices slowed down substantially. Sprint added almost 1 million customers on Clearwire’s 4G network. While this is still a respectable number, it was only half of what Sprint added in the previous quarter. Sprint’s churn numbers are also manageable, with contract churn at 1.99 percent and non-contract churn at 3.68 percent. Despite all the concerns about Sprint’s profitability, Sprint raised $2 billion in debt recently for the 4G LTE network expansion and to help out Clearwire.

T-Mobile had a pretty miserable quarter, losing 706,000 contract customers and a buyer. While the quarter began well with the introduction of T-Mobile’s value plans, the iPhone 4S launch on competing networks, combined with the collapsed AT&T deal, devastated T-Mobile’s hope for a positive quarter. Contract churn increased to a disappointing 3.6 percent–the range in which prepaid operators generally see their churn. T-Mobile’s prepaid churn was 6.8 percent. It is admirable that T-Mobile was able to add 220,000 prepaid customers when faced with such high prepaid churn. In an effort to get churn under control, T-Mobile is planning to recontract a lot of their customers, which is a complete reversal of their strategy of the last several years. In other positive news, T-Mobile was able to increase smartphone contract customers to 11 million or 40 percent of its base. T-Mobile’s wholesale business only declined by 39,000, despite one large customer disconnecting 265,000 lines during the quarter. The overall impact of this customer loss was negligible as these 265,000 lines represented only $1 million in revenues or 30 cents of APRU. A 20 percent increase in data ARPU helped to keep blended ARPU flat at $46. With the spectrum that T-Mobile is getting from AT&T as part of the break-up fee, the company is launching a 4G LTE network in the AWS band. It is able to use the optimal 20 MHz configuration in half of its footprint, with the other half using 10 MHz. T-Mobile is able to compete with this, even better than Sprint, which is initially using 10 MHz nationwide. While building out the AWS spectrum with 4G LTE, T-Mobile will move some of its HSPA+ to the 1900 MHz band. This will open the door for T-Mobile to offer the iPhone in the United States. In the short run, jailbroken iPhones running on T-Mobile will be able to take advantage of HSPA speeds first, giving them faster speeds than Verizon or Sprint customers until everyone will see some Apple 4G LTE love.

Verizon Wireless (NYSE:VZ) had a terrific quarter. It added the most contract customers, by far, in the fourth quarter, with more 1.2 million customers, over 50 percent above AT&T’s tally. The company had its best ever smartphone quarter in its history, with 44 percent of its contract base now on smartphones. Contract churn was near record lows at 0.94 percent. The no-contract segment of Verizon Wireless, which traditionally suffered from benign neglect, showed a nice customer uptick. On the heels of the nationwide rollout of its Unleashed product, prepaid net additions jumped to more than a quarter million. The $50 all-you-can-eat plan gives Verizon Wireless an offer to compete against other unlimited prepaid providers albeit with a quality premium built-in. Verizon had to clean up its connected device database, which led to a decline of more than 1.3 million connections. The company also announced that it has come to an agreement to purchase AWS spectrum that is currently owned by several cable companies; the spectrum covers 93 percent of the United States. While the spectrum is currently idle, Verizon Wireless will be able to use it for 4G LTE services–if the transaction gets approved. Verizon and T-Mobile would create a healthy ecosphere in this spectrum band, leading to lower prices for handset. Ironically, this would help T-Mobile the most even though it has petitioned against the spectrum acquisition. Verizon also expanded its 4G LTE network to 195 markets, covering more than 200 million customers.

Leap Wireless (NASDAQ:LEAP) gained 209,000 voice customers and lost 30,000 broadband data customers for a net gain of 179,000. This was a dramatic improvement from only 10,000 net additions during the third quarter. Interestingly, 65,000 new subscribers were added outside of Leap’s network footprint. Generally, operators try to minimize usage outside their own network footprint because roaming costs make these customers unprofitable. Like almost every other carrier out there, Leap is building its own 4G LTE network. MetroPCS (NYSE:PCS) benefitted from the seasonally strong forth quarter by adding 197,000 subscribers.

US Cellular is still in the doldrums, having lost 13,000 subscribers overall, with 20,000 contract customer losses and gains of 7,000 no-contract subscribers. The problem with US Cellular is that it does not get enough new people in the door as postpaid churn is a healthy 1.5 percent. Hence, the company is looking for a new advertising agency to reposition the company. The Belief Project advertising campaign worked well for the US Cellular customer base but did not inspire the proper belief in customers from other carriers. The good news is that US Cellular’s customers are very satisfied with the company and enjoy one of the best networks. The bad news is that this a very well kept secret. US Cellular is also lagging behind in smartphones with only 30 percent of its customers using one. Its smartphone percentage rose to just above 30 percent; 50 percent of devices sold this quarter were smartphones. The company knows that if it wants to remain a viable provider, it has to compete on 4G. The unlaunched 4G LTE network covers 25 percent of US Cellular’s licensed population, with an expected 50 percent by the end of 2012.

While Clearwire (NASDAQ:CLWR) had a good quarter, with 873,000 subscriber additions, the bad news from its strategic investors keeps piling up: Google announced it is selling its Clearwire stake for $47.1 million, which is a 94 percent discount from what it invested at Clearwire’s inception. To make matters worse, Google was only able to realize a price of $1.60 per share compared to the $2.15 the shares were trading at before the announcement. It is becoming clearer and clearer that Sprint is the only friend left for Clearwire. While its other strategic investors are bailing on Clearwire, Sprint is raising more money for them to give it a chance to surive. How dependent Clearwire is on Sprint becomes clear when we look at the net add breakdown. Sprint added 904,000 customers to Clearwire while the company lost 31,000 Clear-branded customers. This is half of the previous quarter due to Sprint’s focus on the iPhone, and this sends a direct message to Clearwire about how vulnerable it really is.

Tracfone had another great quarter, adding almost half a million subscribers. One of the most interesting developments is that Tracfone, one of the savviest advertisers and notorious for stamping out wasteful spending, has a full-fledged TV campaign for Straight Talk. It is a testament to Straight Talk’s success, product positioning, and widespread appeal that Tracfone is going down that route.