The wireless industry has become a multi-polar competitive industry. The days of the carriers sitting at the center of the universe dictating the orbits of its vendors are over. Looking at just how operators are competing against each other is an overly simplistic way of examining how consumers make their choices and who derives revenues from consumers. In fact, in its most recent report to Congress on the state of competition in the commercial mobile wireless industry, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) provides hundreds of paragraphs and data points that document this reality. “We provide an analysis of whether or not there is effective mobile wireless competition, but refrain from providing any single conclusion because…of the variations and complexities we observe.”1

In this piece, we look at the traditional carrier model that has been commonplace in the United States, the various carriers’ differentiators and sources of profit, the app-centric model of Apple, the ad-centric model of Google, the content-centric world of Amazon, and device manufacturers. What we find is that the competition in the wireless ecosphere is more intense and varied than ever before. While we have a half a dozen players competing against each other in the service provider sphere (AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, Tracfone, Verizon, and the US Government), the device space has three titans, Apple, Google and Samsung, fighting it out like Roman Gladiators with different weapons and positioning. This is compounded by the emergence of a very competitive mobile app market that is as wide open as the PC software market in the 1990s. Since this ecosphere is so interdependent, regulatory intervention has to be well thought through to recognize all possible repercussions and eliminate unintended consequences, as when one segment of the market is interfered with the others will be inevitably impacted.

Companies fundamentally compete in two different ways: By being the lowest cost provider or through differentiation. There can be only one lowest-cost provider and none of the companies we look at, with the exception of Google, is the lowest-cost provider available to their respective customers. As a result, the other players are differentiating and even Google—with the lowest cost operating system—is differentiating itself from its competitors. The more attractive the differentiation, the more value the company can generate from the business relationship with the customer. It is the classic “value for money” exchange.

AT&T is positioning itself as a premium wireless service provider. The company’s main differentiator is its large handset portfolio that gives consumers a wide choice of devices backed up by a large 4G HSPA+ and 4G LTE network. Currently, AT&T offers 92 different devices to consumers and businesses. Giving customers the maximum choice among devices has served AT&T well. When AT&T had the iPhone exclusively it was growing faster than any other carrier. After the exclusivity expired, it still remains the second fastest growing carrier in the US.

Sprint is differentiating around unlimited data, positioning itself as a value provider. Sprint and T-Mobile are the only nationwide operators that still offer unlimited data. Both carriers are able to do this because their networks are comparatively lightly loaded and can therefore accept higher data traffic per customer. Put another way – they have fewer customers than their competitors, and therefore less demand on their networks. The unlimited data strategy is working for Sprint as it is growing its customer base on the Sprint network, whereas Sprint’s technologically obsolete Nextel network continues to hemorrhage customers, resulting in net customer losses. The Nextel network will be closed down in 2013. Sprint’s overall success is hampered by its position as a laggard in the deployment of 4G LTE. The WiMAX network was an interim patchwork solution, but the overwhelming majority of its coverage is 3G. This means that most customers enjoy unlimited data at a significantly slower speed.

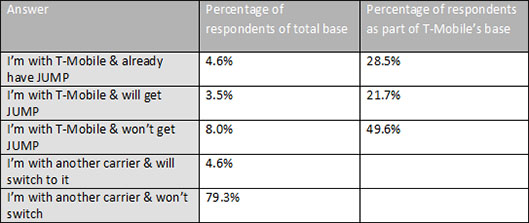

In the midst of a transformation, T-Mobile is positioning itself as a value provider. Before the current plan, T-Mobile suffered customer losses in the last few years as it changed its marketing positioning frequently, even though it offered unlimited data at the lowest prices of the nationwide network operators as customers considered other options as better value for money. On March 26, 2013, T-Mobile introduced its new “un-carrier” positioning. While the price plans were basically a rehash of the Value plans that were released in Fall 2012, the handset pricing came as a surprise. The new $99 upfront fee will make it more affordable for Americans to own new top of the line handsets, which they then pay off over 24 installments. If the new customers actually pay on time for their new devices T-Mobile will potentially benefit quite handsomely by expanding its smartphone customer base to people who can afford only $99 upfront of their handset. If they default substantially more on their devices, T-Mobile will be left with a significant loss.

Verizon has positioned itself as a premium provider differentiating around network quality. The company has always placed greater emphasis on network performance and development than any other carrier in the United States. It launched 4G LTE as the first operator in the world and enjoys a significant lead in 4G LTE coverage. Its network quality leadership has enabled it to be the fastest growing carrier in the United States. By offering customers a reliable network, Verizon Wireless is enjoying the highest customer loyalty in the wireless industry.

Apple is now the number one device manufacturer in the United States. The company has revolutionized the wireless industry with its breakthrough products and provides the best user interface combined with the industry-leading app store. The unprecedented level of handset subsidization that operators provided for Apple devices led to higher customer loyalty to operators. But it also created a previously not seen transfer of profits to a handset manufacturer. As customer loyalty increased and customers flocked to the providers with the Apple iPhone, the power of Apple has risen to a level where it is beginning to disintermediate the operators. With the launch of iMessage, Apple has invaded one of the cash cows of the wireless industry – the messaging business – with impunity. By making iMessage the default messaging provider, Apple is providing greater value for its iOS customer base at the expense of wireless operators.

Google has become the number one device ecosphere provider in the United States with the Android platform. The company provides the Android device operating system to device manufacturers for free. On top of it, Google is constantly improving Android by adding new cutting edge features, generally releasing them every six months. The large scale adoption of Android enables Google to be the premier mobile advertising company in the world with 90%-plus market share in the roughly $8 billion annual US mobile advertising market. The mobile ad market is expected to grow by 50% in 2013.

With revenue figures like that, Google’s bet that building a device operating system would result in advertising revenue has paid off more than handsomely. Apple’s attempt to compete with Google in the advertising segment, which started with a well-publicized foray with iAd, has not had a noticeable impact on Google. By providing a very successful operating system to device manufacturers free of charge, Google has gained significant influence over device manufacturers such that a majority of smartphones are now manufactured according to Google’s specifications for Android.

Microsoft has long been a player in the mobile operating system market with varying levels of success. While it had been a leader in the early 2000s, the introduction of the iPhone and Android found Microsoft being wrong footed and significantly behind the two new leaders. As a result, Microsoft’s Windows Mobile market share has fallen to insignificant levels.

In 2012, Microsoft launched a new operating system for mobile devices, which is competitive with the other leading operating systems. What holds Microsoft back is the embedded base of iPhone and Android users who have spent tens if not hundreds of dollars on applications for their phone and don’t want to buy them again. While Microsoft charges a fee per handset – rumored to be between $30 and $80 per device – Microsoft wants to defend its Windows and Office cash cows. With its renewed push into wireless and now into tablets, Microsoft is fighting for relevance in the post-PC world. Unfortunately for Microsoft, the mobile world has a significantly faster innovation cycle than computers. If Microsoft wants to have a chance in competing they have to release a new version of the phone operating system as often as they change the head of their mobile division, which is once every six months.

Amazon is the dark horse in this race. The company has become the largest online reseller of wireless service in the United States and has entered the device market with its popular Kindle and Kindle Fire tablets. Amazon sells its devices at cost or near cost and aims to make money by selling content for the devices. Once consumers have their devices from Amazon, they are locked into the Amazon ecosphere. The company can tailor their content and software offers around the usage and purchasing pattern of their customers and drive higher sales and revenues through their devices than otherwise possible.

Traditional device manufacturers have been largely relegated to work on other company’s operating systems tied to their specifications and conditions. This reduced amount of freedom has severely curtailed their ability to create significant amounts of profit. Only Samsung has been able to differentiate sufficiently on the Android platform to become significantly profitable. The global handset market, and by extension the US handset market, is far more concentrated than the carrier market.

According to Canaccord Genuity, in Q4 2012 Apple and Samsung accounted for all the profits of the global handset market, with 72% and 29% respectively. In terms of revenue, it is not much better: Apple has 43% revenue share, Samsung 36%, and Nokia 7%. The rest fight over the remaining 5%. The market power that Apple and Samsung have been able to accumulate in the last five years is simply astonishing. The easiest proxy for this are the big wireless tradeshows.

Traditionally, mobile devices were launched at mobile industry tradeshows, which are generally hosted by wireless operator industry associations such as GSMA or CTIA. Everyone was concerned that their news was downed out due to the large amount of news generated at these events. Apple’s decision to have stand-alone events that captured massive media attention and ushered in breakthrough devices with blockbuster sales the other device manufacturers started to desert the tradeshows in favor of their own events. This has basically devastated the tradeshows as there is now a dearth of news and no buzz whatsoever. The buzz these days is around devices and every one of them has decided to have their own party, even though now they probably could have more buzz if they would host a big launch at a wireless trade show.

As each of the competitors becomes more independent of the other, the competitive pressure grows in step as competition increases. Any observer of the Samsung Galaxy S IV launch event could not help but observe that Google was not mentioned once and Android was only mentioned on the spec sheet. Samsung is relegating Android and Google to invisible middleware, while at the same time it prominently mentions the often duplicate Samsung software that replaces Google components in Android and the hardware. Competition does not get much tougher than this.

Another sign of the evolving array of competitors in this space is the emergence of the app segment as a significant value driver. Both established game providers, such as EA and newcomers such as Rovio, are making a significant impact and are generating billions of dollars in revenue. As all of these companies are competing and cooperating with each other, including exclusive arrangements, the level of interaction will increase in lock step with competition in the entire segment. Similar to the messaging segment where Apple has begun competing with the wireless carriers by offering free messaging to all of its devices, we are going to see more and more competition between the app providers, the device manufacturers and the smartphone operating providers on the software side. Apple has eliminated competition on that front by outlawing software on its platform that is replicating, or threatening to improve, Apple software that is integrated into iOS. Imagine the outcry if a wireless operator would have refused to allow iMessage to be implemented as it competes with its text services.

1 Mobile Wireless Competition Report (16th Annual),

http://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2013/db0321/FCC-13-34A1.pdf, (March 2013, 33)

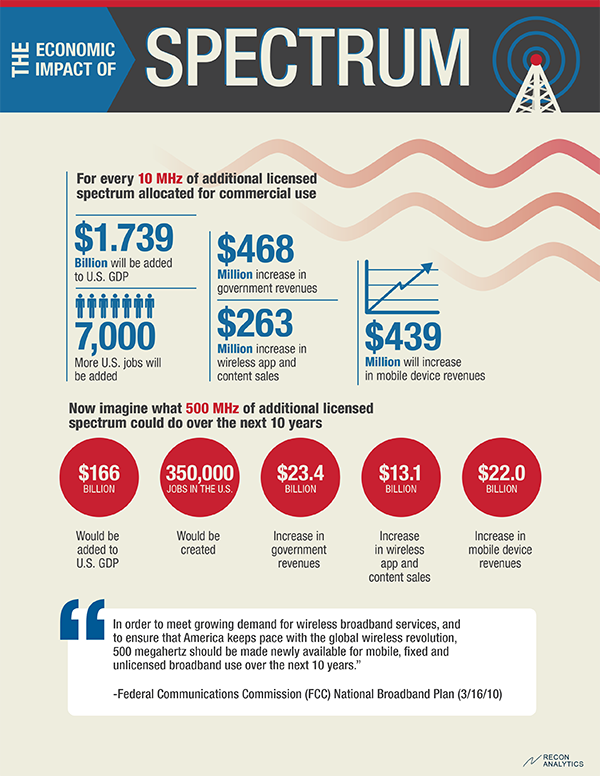

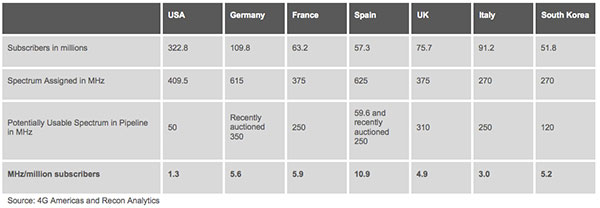

As one can see in the table above, United States mobile operators are facing a significantly more constrained supply of spectrum suitable to support wireless data as compared to their foreign counterparts. When we normalize the spectrum available per person, the United States consumer is by far in the worst position. It has per person, only 1/3 of the spectrum available than Italy where demand for wireless data is comparatively weak. Other countries have assigned three to eight times as much spectrum per person to satisfy the demand for data. Consider the impact on service prices if the FCC really opened up the spectrum spigot. When spectrum was still plentiful in the United States, the wireless operators competed prices to the lowest in the industrialized world. The same competitive forces are at play with regard to wireless data pricing, but could take hold faster and more intensely if more spectrum were put into the marketplace and regulators allowed secondary markets to work more quickly and effectively. Bravo to the FCC for making 30 MHz of WCS spectrum useable for supporting wireless broadband. More and faster decisions like that will go a long way to accelerating the downward price trajectory for LTE based wireless services.

As one can see in the table above, United States mobile operators are facing a significantly more constrained supply of spectrum suitable to support wireless data as compared to their foreign counterparts. When we normalize the spectrum available per person, the United States consumer is by far in the worst position. It has per person, only 1/3 of the spectrum available than Italy where demand for wireless data is comparatively weak. Other countries have assigned three to eight times as much spectrum per person to satisfy the demand for data. Consider the impact on service prices if the FCC really opened up the spectrum spigot. When spectrum was still plentiful in the United States, the wireless operators competed prices to the lowest in the industrialized world. The same competitive forces are at play with regard to wireless data pricing, but could take hold faster and more intensely if more spectrum were put into the marketplace and regulators allowed secondary markets to work more quickly and effectively. Bravo to the FCC for making 30 MHz of WCS spectrum useable for supporting wireless broadband. More and faster decisions like that will go a long way to accelerating the downward price trajectory for LTE based wireless services.