The following is the second of a two-part series examining some of last year’s key developments in the mobile space and also projecting their impact into 2014. In this note, we focus on handsets, operating systems and the networks that support them.

As we consider handsets, OS and networks, a few bottom line conclusions spring to the fore:

- Both the handset market and OS competition are characterized by a sharp divide between two winners and a batch of competitive also-rans. That is unlikely to change significantly this year for either handsets or OS.

- In 2014, Apple and Samsung will continue to account for almost all profit in handsets; Android and iOS will remain the dominant operating systems. Wearables may be the best new growth area (a subject, along with tablets, we will address further in the near future).

- Consumers, however, will continue to benefit from handset innovation, new pricing models for handsets and wireless service, and the opportunities that come with the continued expansion of U.S. carriers’ LTE networks.

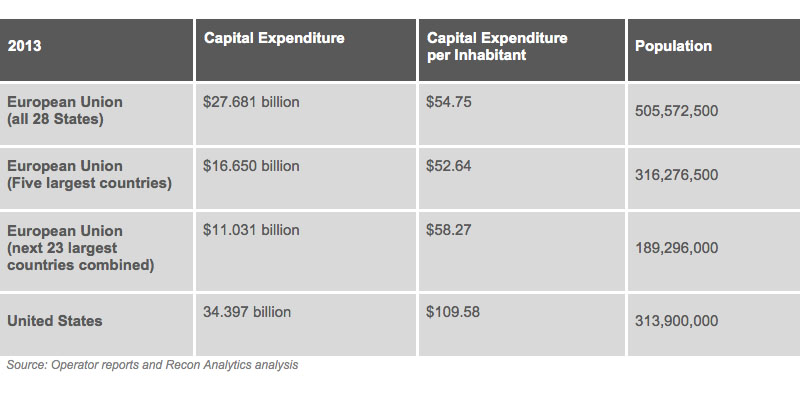

- Fierce competition for network supremacy will mean a continued American edge over Europe in mobile carriers’ capital expenditures and drive further innovation in applications and handsets.

Handset market share in holding pattern

By limiting the opportunity to sell to first-time purchasers who might consider a wide variety of brands, the high ownership levels of smartphones makes it difficult to significantly shift handset market share.

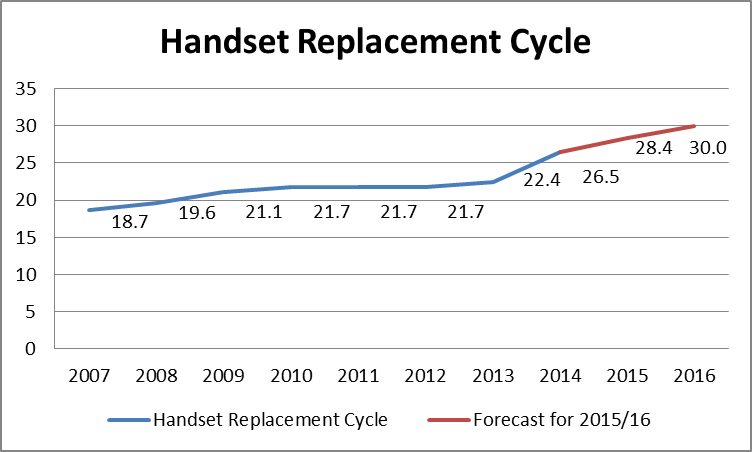

Smartphones now account for more than three-quarter of all U.S. device sales and roughly 90% of the handsets sold by the nationwide carriers. This shift reflects the devices’ astonishing utility combined with declining upfront costs to take a phone out of the store. While Americans upgrade to new devices at a rapid pace (about every 22.4 months in 2013), the data suggests they tend to stick with their current brand rather than switch.

Thus, the introduction of new models such as Samsung’s Galaxy S4, Apple iPhone 5S, HTC’s One and Google’s Moto X in 2013 provided consumers with outstanding new devices, but barely budged market share. The Galaxy S4 and iPhone 5S boosted sales over their predecessors, but because of natural limitations imposed by the law of big numbers the growth rates did not much impact share or impress Wall Street.

Samsung and Apple account for virtually all of the industry’s profits and will continue to slug it out for the championship belt. Everybody else is struggling to stay out of the red. This hierarchy is unlikely to change in 2014 – except for the possibility that some lesser players will exit the marketplace. Indeed, Google has already run up a white flag in handsets with the sale to Lenovo of Motorola Mobility’s handset division (although retaining most of Motorola’s patent trove). Overnight, the transaction makes Lenovo No. 3 in the battle for handset supremacy and endows it with an outstanding piece of hardware, the Moto X phone. A strong marketing effort and long-term commitment to the brand may give Lenovo a chance to make inroads – but it won’t happen suddenly this year.

Microsoft’s 2013 acquisition of Nokia represented a bid to replicate Apple’s integrated approach of keeping both its software and hardware in house. So far, the effort is lagging in the marketplace despite good quality. Things remain dire for BlackBerry, where device sales have imploded and the company is hemorrhaging cash in an unsustainable way. HTC, one of the other premier device brands, is continuing to lose money in its core device business in what looks increasingly like a race against time.

Feature phones headed for oblivion?

Nor is there much opportunity in feature phones. With fewer and fewer people shopping for these phones, the variety and innovation in this segment is on the decline – and so is its price advantage over more advanced phones. Slowly, but surely, feature phones are headed for near extinction in the United States. Even in emerging markets, feature phones are likely to yield the field as manufacturers produce a more diverse inventory of smartphones to fit a variety of individual budgets.

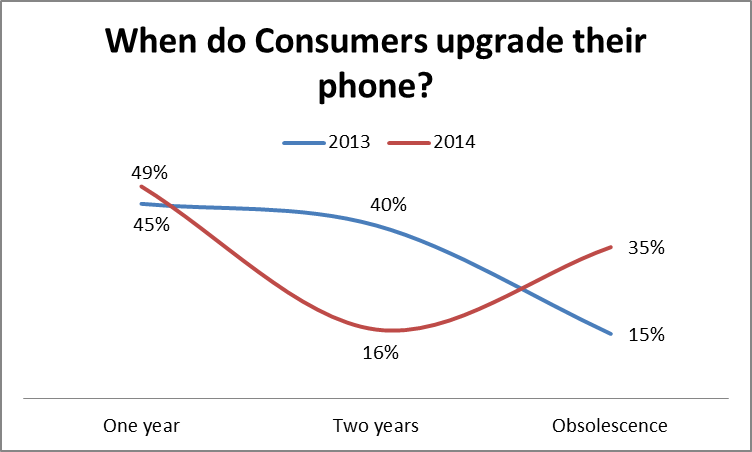

The demise of the feature phone is being accelerated by the emergence of handset financing and enticing trade-in options for smartphones. More and more consumers are taking advantage of phone financing offers or opting to trade up sooner in exchange for cash and/or credit toward new devices. While these programs actually include restrictions similar in kind to the subsidy model they are replacing, consumers are attracted to lower out-of-pocket costs. With a financing plan, consumers can walk out of the store with a high-end smartphone for zero down and between $24 and $27 per month – so they see little reason to settle for less than the best. Although they may pay more for their device in the long run under the new plans, consumers like the idea of paying in smaller increments compared to plunking down $200 up front for a subsidized device under the traditional service contract.

Minting a winner is increasingly a matter of marketing

Increasingly, the dividing line between the winners and losers in the handset business in the United States comes down to marketing. Apple and Samsung have been willing to make the necessary $150 million plus annual spend to create and sustain a consumer brand. The market laggards’ promotional efforts, on the other hand, have been episodic and underfunded. Instead of continuous year-round advertising to implant their brands in consumers’ psyches, competitors have largely run ads in short spurts or around specific events. As quickly as the ads appeared they disappeared, and so did public interest in their new offerings.

Microsoft, for one, certainly has the wherewithal to sustain prolonged campaigns, but has chosen not to do so for its mobile offers. Given the limited effect of its underfunded marketing efforts, it might have been better off skipping it altogether. Accelerating the device upgrade cycle might crack the door a bit for possible inroads because the more times a consumer goes to the store, the greater the chance he or she will decide to switch. But so far that has not happened even though Americans change their phones more often than consumers elsewhere around the world.

Still, this comparatively rapid handset upgrade cycle has propelled the United States to the leadership position in the global smartphone economy. New devices with new capabilities drive the demand for faster and better networks, which, in turn, make new applications feasible. That’s what keeps the mobile space in the United States so exciting. In contrast, consumers in continental Europe replace their devices every four to six years, which traps them in the digital past. Just imagine still using the first generation iPhone: magical, revolutionary, but oh so six years ago.

Aside from potentially opening the door to movement in market share among device makers, a shorter upgrade cycle matters because new, high quality devices boost customer satisfaction. That satisfaction spills over to network providers whose high-speed data networks open up new possibilities for mobile devices. Satisfaction reduces churn among carriers and supports a comparatively high average revenues per user as customers receive good value for their money. The result is a virtuous “win-win-win” circle that should hold even with changes in the way customers buy services and devices.

OS market looks steady

Stability is also likely for OS market share in 2014. The two OS leaders, Android and iOS, hold about 90% of the market between them and, will continue to jockey for position. Windows Mobile, a good if unloved system, has likely hit bottom and should gain slightly in 2014, especially in the prepaid market where it has done relatively better. BlackBerry is still trending down. Absent a game-changing device (which we do not expect), BlackBerry could slide further this year. Other systems are little more than background noise.

Google’s decision to sell its handset business may boost Android by removing handset makers’ concerns about competing with a Google phone even as they embrace Google’s flagship OS. In that sense, its deal with Lenovo may be seen as a renewed commitment to a multi-vendor Android ecosystem. By contrast and absent a change in direction under its new leadership, Microsoft appears committed to both its Nokia handsets and its Windows Mobile OS.

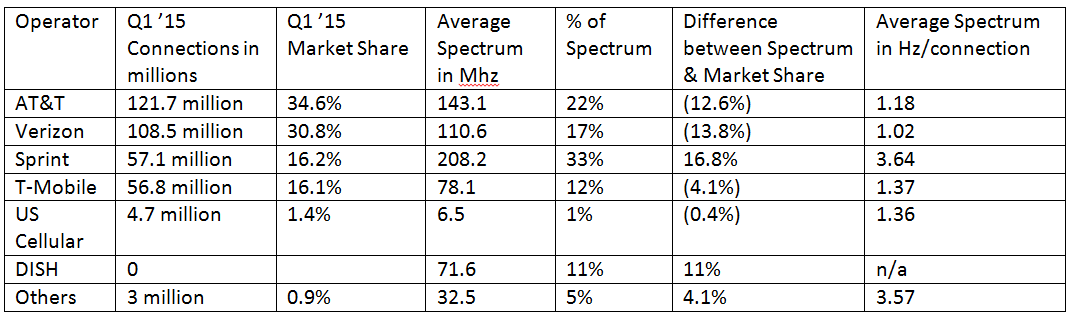

The usefulness of these devices and operating systems are contingent on strong networks with the capacity to handle rising demand. As noted in part one, U.S. carriers are locked in a feverish race to expand their LTE footprints and also increase speeds. Among the key questions is whether Sprint, which is spending lavishly with new money from Softbank, can make it a four-way competition. In our view, 2015 is the year that Sprint’s networks will match or exceed its rivals by taking advantage of its huge spectrum holdings.

Devices and the networks that make them work

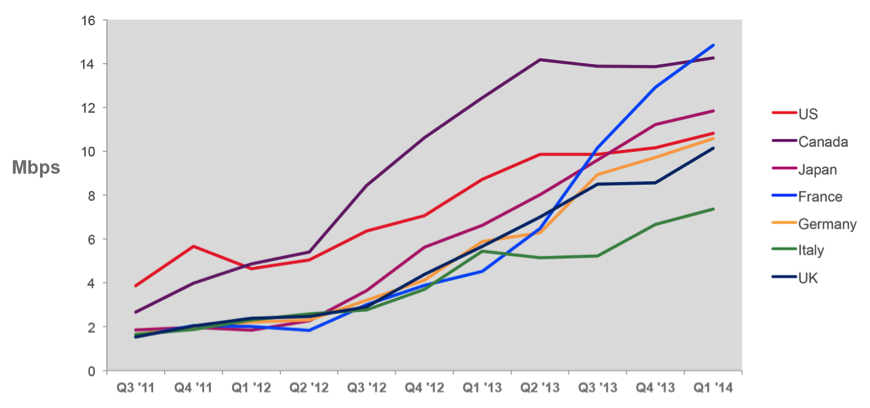

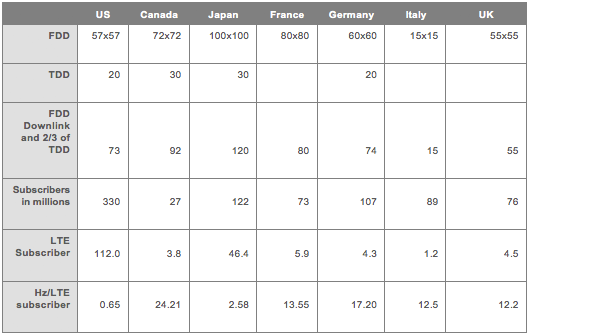

The United States is home to more than half of all LTE subscribers in the world and carriers continue to pour money into their networks. In 2013, AT&T and Verizon Wireless combined easily outspent all 58 European wireless carriers combined. The U.S.-Europe gap is even greater when increased investment by T-Mobile US and Sprint is toted up.

Verizon Wireless has the largest LTE network, covering more than 90% of the U.S. population. But the company’s competitors are challenging its supremacy and increasingly claim to exceed Verizon Wireless in speed, reliability or both. Those claims have gained credibility because of several nationwide LTE outages that have hurt Verizon Wireless’ reputation. But the carrier is bringing additional spectrum online, which should boost performance and help it hang on to its reputation as number one.

AT&T is catching up through its multi-year Velocity IP initiative. AT&T is spending more than $10 billion a year on its wireless network and now reaches about 280 million consumers with LTE. By mid to late 2014, AT&T Mobility should match Verizon Wireless’ network in coverage. AT&T Mobility will get a capacity boost in 2015 as it deploys additional 2.3 GHz (WCS) spectrum.

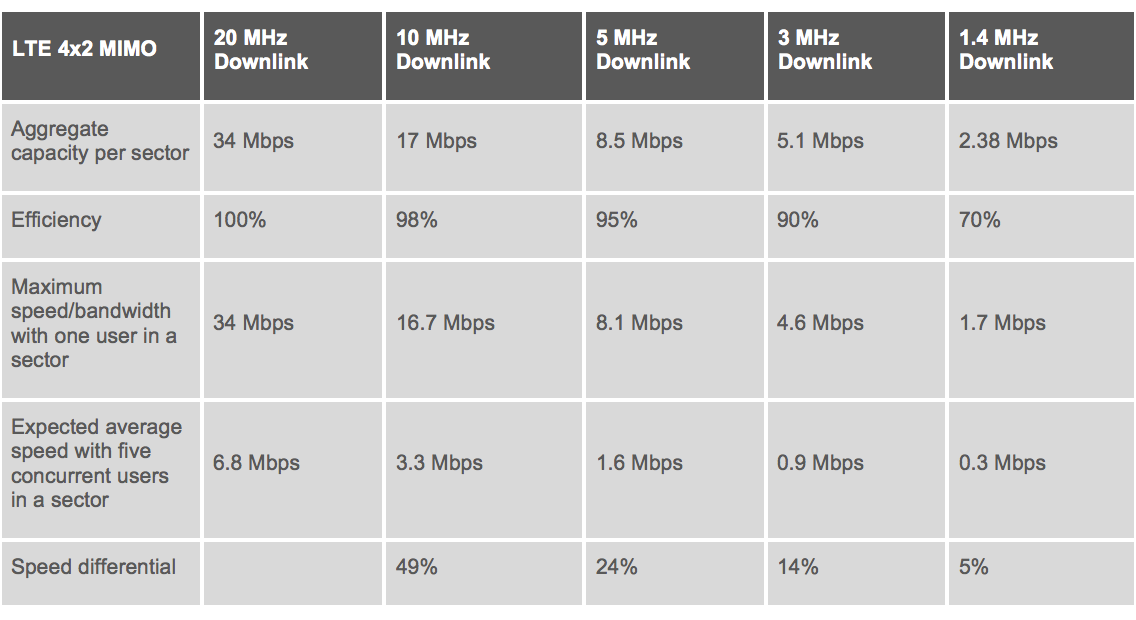

T-Mobile US has put the pedal to the metal and now covers 200 million consumers with LTE. It’s also claiming the fastest speeds in half of the top 20 markets and points to a Speedtest.net study to claim the overall crown for fastest downloading. Backhaul upgrades in 2012 and 2013 and new spectrum acquired from MetroPCS have positioned T-Mobile US with 40 megahertz of spectrum to support LTE. The company cleverly minimized zoning hurdles by reusing existing antennas and focusing only on existing sites to optimize the beefed up network. The company faces a bit of a catch-22 going forward, however. Its comparatively lower number of customers per-megahertz of spectrum provides higher speeds, but download speeds will drop as its customer base expands and puts greater demand on share resources. One way to mitigate that trend is a quicker shift of former MetroPCS customers from that company’s legacy CDMA network to T-Mobile US’ GSM/HSPA/LTE network, so we expect speedy migration will be an operational priority in 2014.

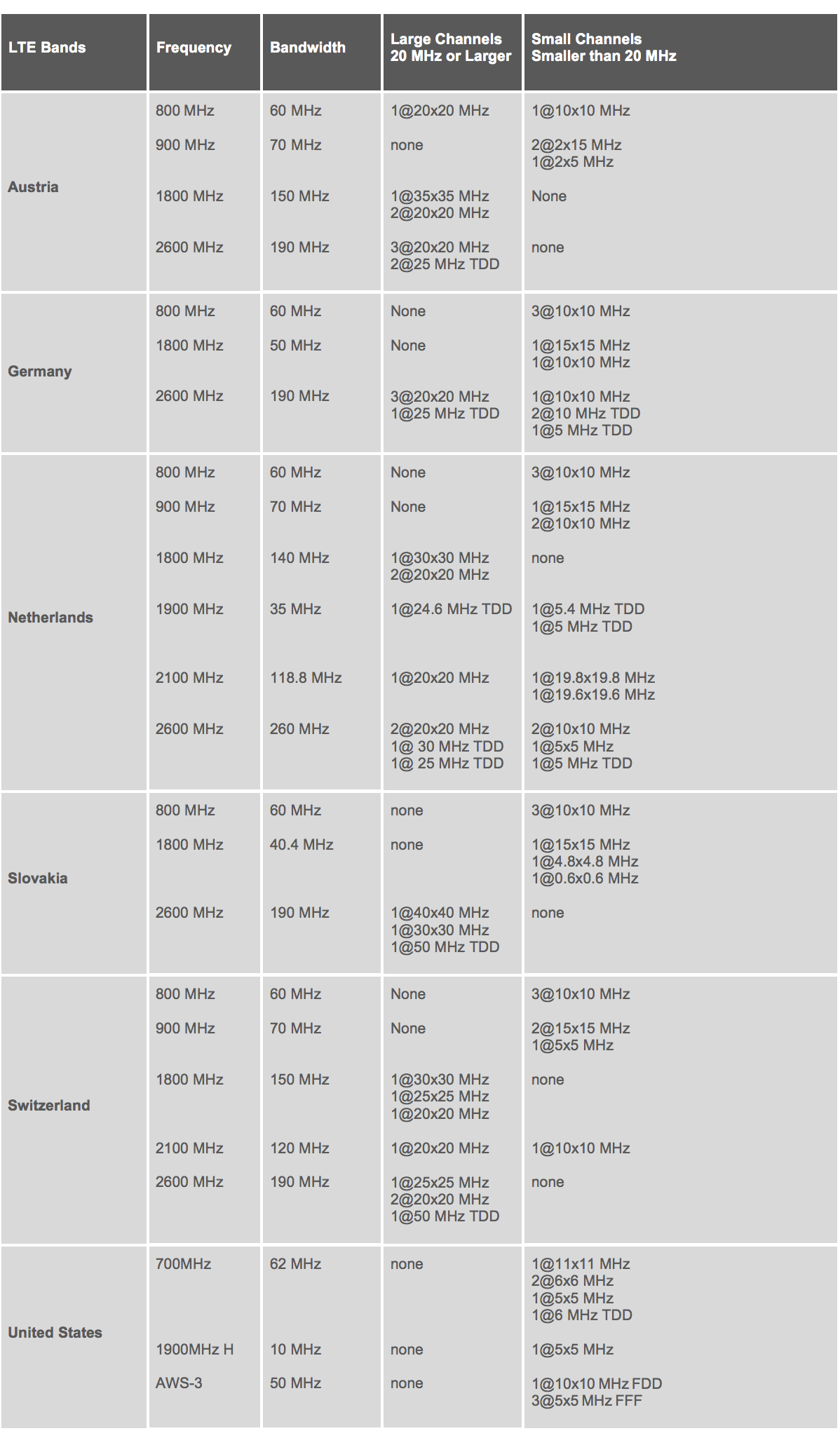

Sprint’s network upgrade is not going as well. Sprint now covers about 200 million consumers with LTE, but quality has declined because of disruptions created by the longer-term network upgrade. The company is replacing all of its base stations and antennas, creating a massive local zoning and permitting nightmare and knocking the effort off schedule. Once past these obstacles, however, Sprint should be better positioned. Sprint Spark will aggregate several 20-megahertz contiguous channels to achieve initially industry leading speeds. The company has launched a few markets and expects 100 million pops covered for Spark by 2015. Given the potential competitive benefits from Spark’s speeds, we’re disappointed that it’s projected to cover only 100 million consumers in 2015. Finding some way to accelerate deployment would provide a major boost for the company’s competitive position.

Even regional carriers are investing in LTE to remain competitive. U.S. Cellular is currently covering 80 million pops with LTE, which is 87% of its footprint. C Spire also has aggressively expanded its LTE footprint.

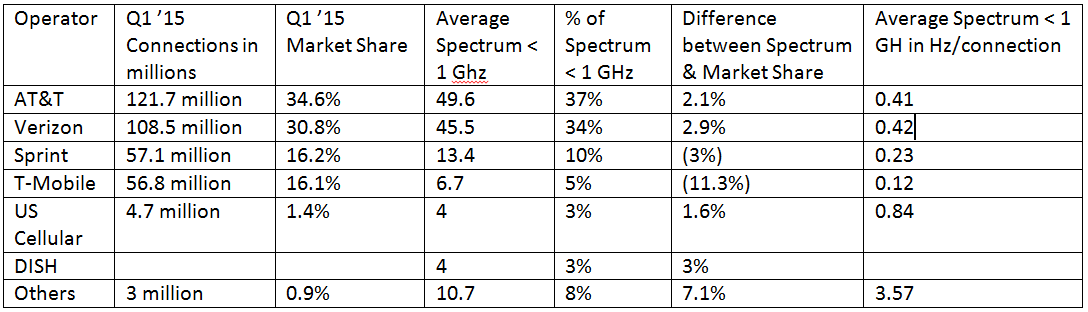

The future of the various networks is, of course, tied to spectrum and how efficiently carriers put it to work. Given the continued growth in data demand, which is now climbing about 50% annually, putting more spectrum in the hands of wireless carriers is now a Federal Communications Commission priority. Curiously, the big winner from Auction 96, which began in January, is almost certain to be Dish Network rather than one of the national wireless carriers – none of which is bidding for the 10 megahertz of 1.9 GHz (PCS) spectrum now available. As of right now the bids for Auction 96 are coming in at $1 billion, still well shy of the $1.56 billion Dish Network has promised to pay for the nationwide license.

The big action in spectrum is the voluntary auction of TV broadcast spectrum that the FCC will shift to wireless broadband providers in 2015. The outcome of that auction may depend on the commission’s bidding rules, which is now the focus of a fierce debate among the national carriers. A successful auction also would provide critical funding for the planned public safety network, FirstNet. The usability of the 700 MHz A-Block also is at stake as the incentive auction will remove the Channel 51 interference.

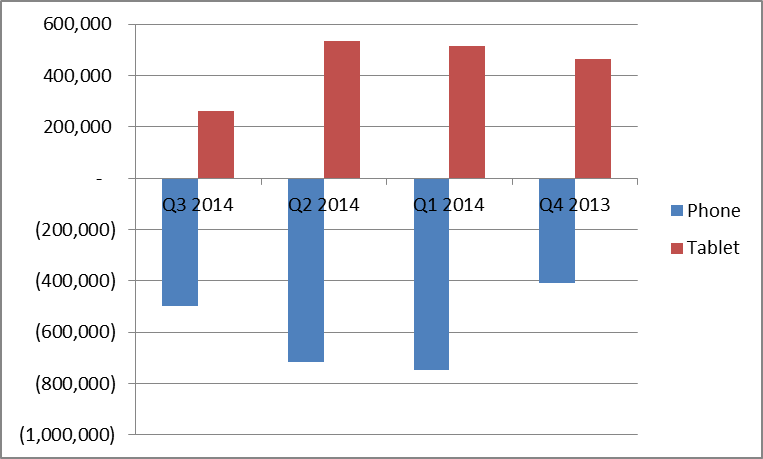

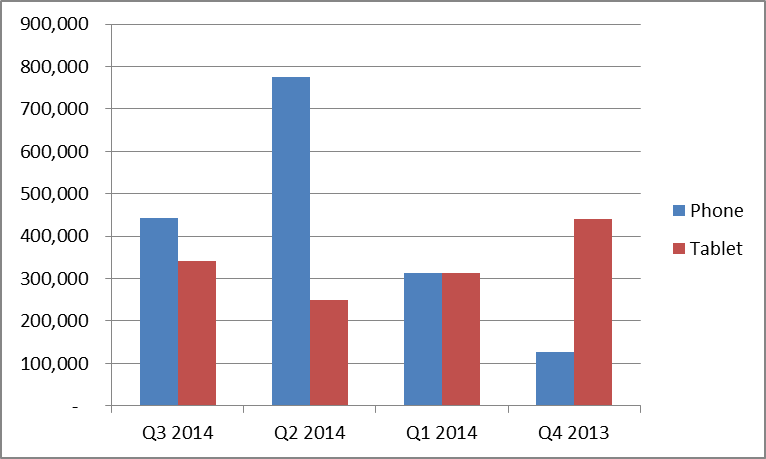

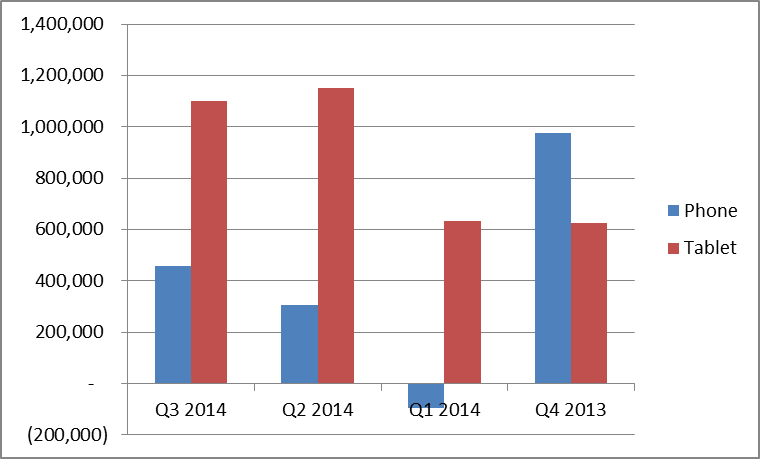

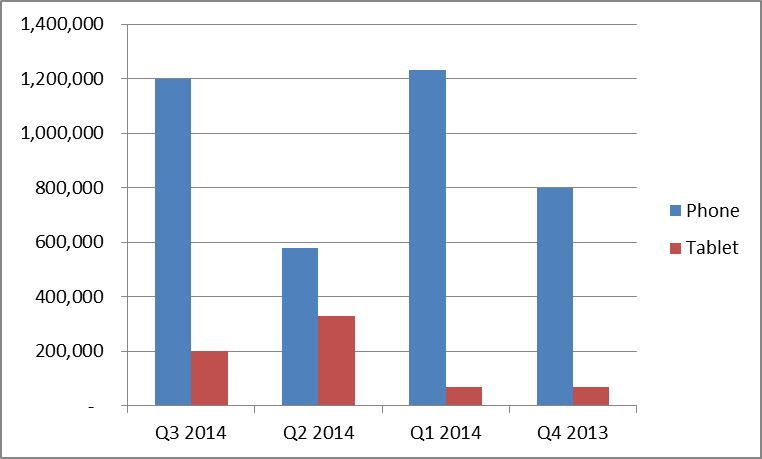

Source: Recon Analytics and Q1 2014 operator reports, 2014

Source: Recon Analytics and Q1 2014 operator reports, 2014