In 2014, roughly 143 million mobile phones were sold in the United States, approximately 90% of them smartphones. This is a decline of 25 million phones from 2013 when approximately 168 million phones were sold – and only half of them were smartphones. The decline in phone sales is predominately due to the rise of equipment financing plans, compounded by slower new subscriber additions. At the same time, consumers’ phone purchase habits have changed significantly. A growing number of American consumers delay their phone upgrades to take advantage of the lower monthly service prices carriers offer to consumers who wait to upgrade phones at the end of their two-year contracts.

Consumers who are purchasing replacement phones are focusing on newer, higher priced devices. Even though device sales declined by 15% year-over-year, device revenues increased by about 5%. In the short term, this flight to higher priced devices increases revenues and profitability for mobile carriers, but longer-term the trend is negative, as it takes longer for new devices to permeate the network. Device manufactures are cheering the higher revenues as the market has shifted heavily towards higher priced smartphones. Now that smartphones make up 90% of handsets sold, device manufactures can no longer cannibalize feature phones for significant revenue upside. We expect device sales to fall by 5% to 136 million in 2015 and to fall again by 4% to 131 million in 2016.

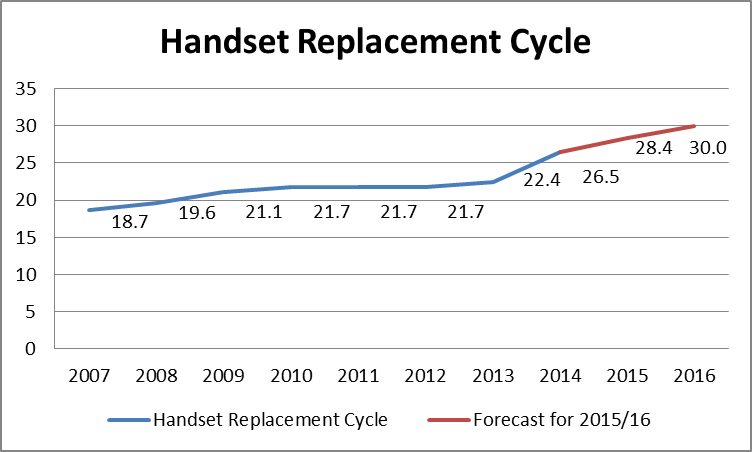

With device sales and new subscriber additions declining, the impact on the handset replacement cycle has been significant. Handset replacement has abruptly slowed to the lowest rate since we began calculating the metric. The introduction of Equipment Installment Plans (EIP) has made a significant impact on the handset replacement cycle by extending it to 26.5 months in 2014, an increase of 4.1 months compared to the previous year.

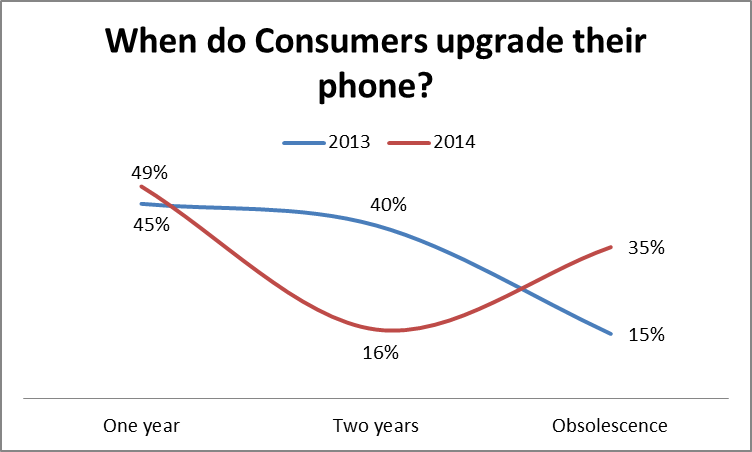

Americans typically upgraded their phone at three points in time: Roughly every year when a new generation device was launched; approximately every two years when the contract expired, causing customers to either change operators or became eligible for subsidized prices; or whenever their phones became obsolescent or stopped working. With the rise of EIP plans that incentivize both rapid upgrades every year and delayed phone upgrades through discounted service pricing, consumers have eschewed the traditional two-year service plan upgrade cycle.

The percentage of devices being replaced every year increased from 45% in 2013 to 49% in 2014, while the percentage of devices that replaced obsolete devices sky rocketed from 15% in 2013 to 35% in 2014. The percentage of devices being replaced at the traditional two year time point fell from 40% in 2013 to 16% in 2014, while they represented slightly more than 50% of replaced devices from 2010 to 2012. As As Americans bifurcate their purchasing behavior, we are observing the beginning of a capabilities gap between Americans who upgrade their phone every year and those who upgrade it when the device becomes obsolete or breaks.

The handset replacement cycle measures how often existing customers are upgrading their phones. It is an important measure of how close the average consumer’s device is to the technical state–of-the-art. Whereas most consumers used to upgrade after two years, today’s market sees an interesting dichotomy: Nearly half of consumers upgrade every year, but more than a third keep their devices until they become obsolete. A longer handset replacement cycle will have several ramifications on innovation throughout the mobile ecosystem:

- Less innovation in applications: Application capabilities may be artificially restrained, as developers deal with an average consumer who is less able to take advantage of new technologies that improve the utility of the device and service. The introduction of EIP has created an earthquake-like, tectonic shift in when Americans are upgrading their mobile phones. Software developers face a new dilemma, as they must nowgrapple with the fact that a large percentage of smartphones in use won’t be able to run their new cutting edge apps. In order to run on the largest number of devices possible, some developers won’t build the latest-and-greatest capabilities into their apps, thereby slowing the pace of innovation in the mobile space.

- Less competition from smaller handset providers. Most handset manufacturers – who are already struggling to remain profitable – will be under pressure to cut their research budgets as revenues decline, therefore reducing the amount of effort dedicated to making the next generation smartphones even better. Smaller handset providers are going to be disproportionally hit, making their devices less competitive compared to larger handset providers — leading to a shakeout.

- Spectrum crunch in major markets. The spectrum crunch in major markets will be worse than otherwise as older devices cannot access new spectrum bands as they are lacking the necessary electronics for it. Device capabilities determine which network capabilities the phone can access. A six year old iPhone 3G will achieve download speeds of 2 Mbps with its first generation WCDMA chipsets, whereas a new iPhone 6 will be able to download the same content 25 times faster due to its new 4G LTE capabilities able to access newly licensed spectrum. As fewer people upgrade their devices, the pace with which consumers can use new unused parts of the networks on new spectrum slows down and consumers are stuck on congested legacy spectrum. This engineering reality is particularly important as mobile operators are currently spending more than $45 billion on new spectrum.

- Delayed transition to next-generation services. The monumental transition to VoLTE — and therefore to a more efficient use of spectrum, with significantly better voice quality — will be slowed by an embedded base of older devices.

To be sure, despite the bifurcated market and all the problems caused by it, some positive developments could still increase revenue for manufacturers:

- Speed boosts. Faster speeds mean access to better and more content and higher profits for web retailers and carriers alike. The faster the download speeds a device can support, the better the user experience as the consumer does not have to wait for video content to be buffered or web sites to be loaded. According to Akamai, a one second delay in page load results in a 7% decline of purchase conversion.

- More power. Access to more advanced screens and processors allow more appealing graphics and more powerful applications to run on your phone. This begets more usage and more consumption of content which in turn generates more revenue and profits for multiple entities across the mobile broadband value chain.

- Better batteries. Newer battery technology allows phones to run longer allowing them to be used to do more for a longer period of time. This too impacts the virtuous cycle of more use begets more revenues and profits.

Unfortunately, those longer-term developments could be largely offset in the short term by the slowed innovation and cramped spectrum caused by delayed handset replacement.

Who are short-term and long-term winners and losers in this change?

- US Consumers: Short-term winner, long-term loser.

Consumers get $20 per month more in their pocket for waiting to upgrade their phone. In the longer term, consumers will have fewer choices and delayed mobile phone innovations and fewer new apps taking advantage of new hardware features than they would have in a higher volume scenario with more device manufacturers. - The US (app) economy: Short-term winner, long-term loser.

While an approximately $12 billion per year (50 million devices times $20 per month) in additional stimulus for other the rest of the economy is helping boost restaurant sales and reducing consumer debt, the economy will feel the long-term negative impact. As consumers and businesses alike are tempted to delay an upgrade, the beneficial impact between mobile and productivity in the US will weaken as new services that save us money, improve our lives, and make the economy more efficient take longer to be implemented. One especially poignant example is mobile payments. ApplePay is revolutionizing mobile payment with high attachment rates because people with the new iPhone 6 can take advantage of ApplePay. People who delay cannot, creating a barrier to adoption. The same is true for NFC (or not) enabled devices for other mobile payment platforms like PayPal or Google wallet. - Device manufacturers: Short-term winner, long-term loser.

Device manufacturers benefitted handsomely as smartphones as a proportion of handset sales increased from roughly 50% in 2013 to 90% in 2014 and profits surged. In 2015 and onwards, profits will fall as the number of devices will continue to decline - T-Mobile: Short-term big winner, long-term loser.

T-Mobile successfully reshaped the mobile industry through the introduction of its EIP, and has grown faster than all other carriers combined. At the same time, roughly 30% of its new customers did not buy a new handset, but brought their own. As a result, the handset base is aging and cannot take advantage of new bands like 700 MHz and VoLTE. The introduction of SCORE! has to be seen in the context that T-Mobile wants to speed up the handset replacement cycle, and is willing to incur a modest subsidy. - AT&T: Short-term winner, long-term loser.

AT&T followed T-Mobile aggressively into the brave new EIP world. AT&T has been able to defend its base against lower priced T-Mobile and other operators who offer EIP financial benefits as device subsidy expenditures have declined significantly. AT&T will face the same problems as T-Mobile as the device universe of its customers ages. - Verizon: Short-term neutral, long-term neutral.

Verizon is holding on as tightly as it can to the status quo, while offering customers who want it an option to do EIP. In the short term, Verizon benefits less than T-Mobile and AT&T from the changes, but will also not suffer as much from a lengthened handset replacement cycle. - Sprint: Short-term loser, long-term winner.

Sprint, like every other company, dabbles in EIP offers, but only Sprint with its 24-month handset leasing program has a viable plan in place to keep the device upgrade cycle in place and reap the benefits from a customer base with newer devices.